The term tax-exempt can be misleading. Although not-for-profit organizations are able to obtain an income tax exemption from the IRS and other state tax authorities, taxes on payroll, property, and sales are still collected. Additionally, private foundations are required to pay tax on their investment earnings.

The term tax-exempt can be misleading. Although not-for-profit organizations are able to obtain an income tax exemption from the IRS and other state tax authorities, taxes on payroll, property, and sales are still collected. Additionally, private foundations are required to pay tax on their investment earnings.

The ultimately low tax rate faced by private foundations often means tax planning isn’t a priority. However, through various distribution and planning opportunities, a foundation can reduce its tax burden while increasing its impact on not just the community it serves, but its own vitality.

This article is the second in a series taking an in-depth look at topics important to private foundations, including self-dealing, excess business holdings, and private operating foundations.

Calculating Net Investment Income

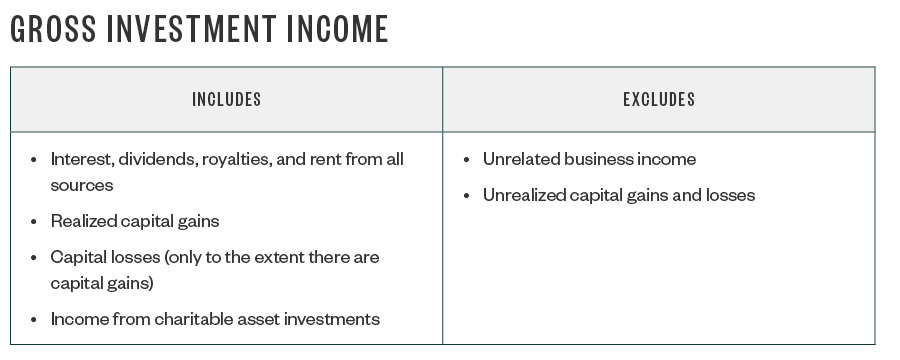

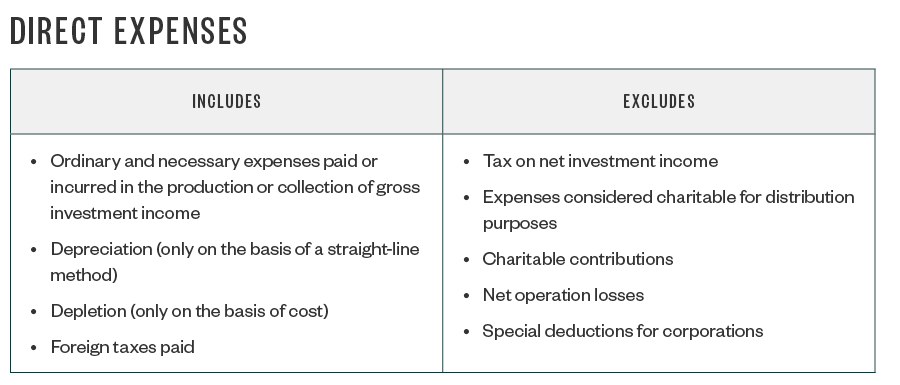

The investment income excise tax applies to most domestic tax-exempt private foundations. Taxable net investment income is calculated by deducting direct expenses from gross investment income. Both terms are defined in the following tables.

To the extent a private foundation’s gross investment income exceeds the allowable deductions, its net investment income becomes subject to a 2% tax under IRC Section 4940(a). Organizations not subject to this tax:

- Certain electing grant organizations exclusively organized and operated to make grants to educational organizations

- Exempt operating foundations organized and operated like public charities

Cutting Your Taxes in Half

Private foundations have the opportunity to annually reduce this tax liability from 2% to 1%. This might not seem like much when a foundation only sees a $500 reduction, but as its endowment grows and investment income increases, this 50% reduction can represent hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A private foundation focused on reducing its tax rate can do so by ensuring its payout ratio—calculated by dividing total qualifying distributions by the value of noncharitable use assets—exceeds the average payout ratio for the past five years plus 1% of its net investment income.

This means a foundation can reduce by 50% its current year income tax liability by adjusting the timing of grants and charitable expenses to increase qualifying distributions in excess of the prior year’s payout ratio.

This isn’t a sustainable strategy for most private foundations, however, because qualifying distributions would need to annually grow at a rate that would likely begin to deplete a foundation’s corpus.

Minimum Distribution Requirement

The IRS imposes a minimum distribution requirement on private foundations of 5% of the value of all noncharitable use assets. This distribution requirement is due to the closely held nature of private foundations, which don’t have as much public oversight as public charities, and helps to ensure charitable assets are spent and not held in endowment.

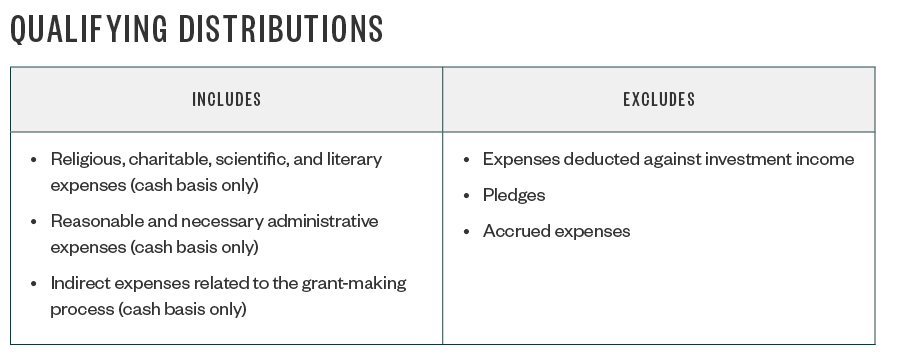

Qualified disbursements are defined in the following table.

Program-related investments and charitable asset purchases are added to these charitable disbursements to determine a foundation’s total qualifying distributions. Any repayment of cash disbursements, including returned grant funds or repaid program-related investments, count against a foundation’s distribution amount.

Timing

A foundation has until the end of the subsequent tax year to distribute its current year’s minimum distribution requirement. If it still fails to meet the requirement, the IRS assesses a 30% tax on the gap amount, which can increase to 100% if not remedied by the foundation in a timely fashion.

A foundation that distributes more than the 5% requirement can carry that excess forward for up to five years.

Tax Planning

A foundation that’s able to weigh investment income and asset growth against its current spending plan can often identify trends during the tax year by asking these questions:

- Was there a large sell off or transfer of investment assets in the current year?

- Is there a reason investment income might spike?

- Was there a drop in the stock market with heavy realized and unrealized losses?

For example, a foundation might consider cutting back charitable distributions if its investment income decreases. While the foundation would still need to meet the minimum distribution requirement, it could employ tools to avoid violating the IRS’s mandate, such as:

- Using excess distribution carryovers from the past five years

- Deliberately not meeting the minimum distribution requirement until the succeeding year

Both of these options can provide private foundations with more attainable future tax savings while also protecting corpus in a year when asset values drop.

We're Here to Help

For more information on how tax planning can benefit your organization, contact your Moss Adams professional.